Writers & Lovers by Lily King – Casey wants to finish her novel, a project she’s been working on for six years, or possibly her whole life. She only dates writers, waitresses, hides from student loan collectors, and keeps moving (except when she can’t move at all) to escape her anxiety and the waves of grief over her mother’s death. A book about writers writing holds potential for over-thinking, but I loved the way the various writers relate to Casey, her work, and their own work. King captures anxiety and grief so well, they’re linked to the characters in a way that authentically shapes their relationships with themselves and each other. There’s a lightness and wry humor to King’s style that explores ego, systemic and personal misogyny, and the way people continue to surprise you with their selfishness and caring. You can see the potential for a few different endings for the story, which I appreciated, and I enjoyed the tinges of hope and progress that pepper various parts of Casey’s story.

The House in the Cerulean Sea by TJ Klune – When a lonely government employee receives an assignment of a lifetime (investing one of the many orphanages he’s investigated in his role as Case Worker), he finds his governmental role, his normal routine of distancing himself from his work, and his overall place in the world to be in question. The writing is whimsical and lovely, even when describing the most dangerous of magical children, which made reading this rather delightful. The themes of acceptance and love aren’t hidden in the least. I found it interesting to explore the role of empathy as a motivator and an alibi for participating in actions that aren’t systemically empathetic, kind, or moral.

I discovered the controversial inspiration for this story (the Sixties Scoop) after reading it. The messages in the story still hold for me, for the most part, particularly the details surrounding acceptance and inclusion. I think reading this, particularly in middle school, could be an excellent discussion starter regarding the role of historical events in fantasy stories and how to look critically at writing done about historical events that doesn’t come from a community member represented in those events.

Our Missing Hearts by Celeste Ng — After reading The School for Good Mothers last year, I wasn’t sure I had the emotional bandwidth to dive into a book about “re-placing” children whose parents deviated from the accepted line of thought in the United States. At first glance, upholding American traditions seems vague enough to be innocuous – until it’s vague enough to be malicious. As Bird Gardner learns more about his mother, a poet who seemingly abandoned Bird and his father, he begins to question how he moves through American as an Asian-American, and what that means to the people he encounters. What kept me immersed in this story, above all else, is the way Ng writes about the role of art, specifically storytelling, as an act of resistance. While technically dystopian, it didn’t read exactly like that to me, especially during a time when my personal community is mired in discussions about book banning and how history should be taught in schools.

Once There Were Wolves by Charlotte McConaghy — Despite my propensity for posting zoo content on my Instagram stories, I don’t know all that much about animal conservation. I know next to nothing about forest re-wilding, nor the twin bond, nor did I know anything at all about mirror touch synesthesia, yet I fell in love with this story quickly and thoroughly. (Also, I know there are wolf conversations happening in Michigan, and I should probably keep track of them a little, but see the above review about school board issues and where my attention lies at the moment.) The way Inti’s passion for wolves and the forests they protect tangle together with the way she views the people around her, including her twin sister, Aggie, make McConaghy’s story a visceral look at the way people damage each other and the world around them, while inadvertently harming themselves. With the mystery of a bad man’s death tainting the reintroduction of wolves to Scotland, Inti needs to face how her past, her parents’ pasts, and her own reluctance to trust anyone but her sister will have repercussions for the animals she is trying so desperately to save. I can’t remember who recommended this one, and I wasn’t sure how I would feel about it when I began, though I should have know, given how much I like tension and flawed characters in a story.

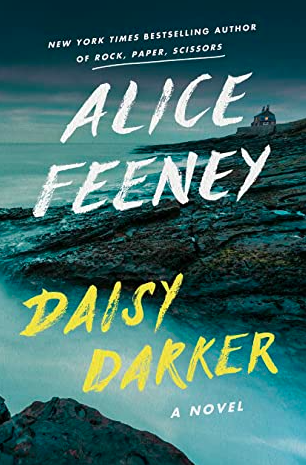

Daisy Darker by Alice Feeny — You know there’s bound to be drama when an estranged family gathers together for an eccentric matriarch’s 80th birthday. Feeny raises the stakes in Daisy Darker by housing Nana in a rambling old home on a remote causeway and making sure the reader knows a fortune teller once predicted her 80th birthday would be her last. Family secrets crowd around the gathering, where Daisy, and possibly her sweet niece Trixie, seems to be the only one who truly appreciates her grandmother. As the night progresses, it reminded me of a favorite Agatha Christie mystery, one that is later referenced in the story. The story twists and turns, leaving everyone at risk of being killer — or suspected of being the killer. I enjoyed this one, especially as a pure bit of thriller escapism.